Health Stories & the Communities that Hear Them

March 8th, 2016

Stephanie Huston, Director Community Development

We, as humans, are natural story tellers. Even our most basic communications are often expressed in the form of a narrative. “A narrative account involves a sequence of two or more bits of information which are presented in such a way that if the order of the sequence were changed, the meaning of the account would alter”1. We apply this, and multiple other indicators, all the time. Temporal changes, tense variation, climaxing topics, learned morals — we incorporate these elements into much of our daily conversation without even realizing it. And we come to digest and remember our experiences based on repeated narration. Essentially, our memories and experiences are understood and ingrained through story telling.

But much like the tree in the woods, is a story told to the wrong audience ever really heard? Whether it’s shared misery you seek, mutual understanding, or exchanged tacit knowledge, the right community is essential for the success and catharsis of a story.

Our health experiences are no exception. How we believe, remember and recollect our health — or lack there of — is framed by our narrative communications.

For a time, our health experiences were only “freely” expressed within the confines of a professional office setting. I use quotations because even at the point of practice, in an environment dictated by health and wellness, we still aren’t really free to tell our stories. Research has shown that patients actually only get about 12 seconds of speaking time before being interrupted by their physicians2. But the development of the Internet and social media has revolutionized our expression of individual health stories and experiences. Where we once had a limited, strictly diagnostic space for narrative health expression, we now have an open, uninhibited, and often anonymous, online world of stories.

But even with the entire Internet at one’s disposal, without the right community with whom to share the story, is it really heard? Is it really embraced?

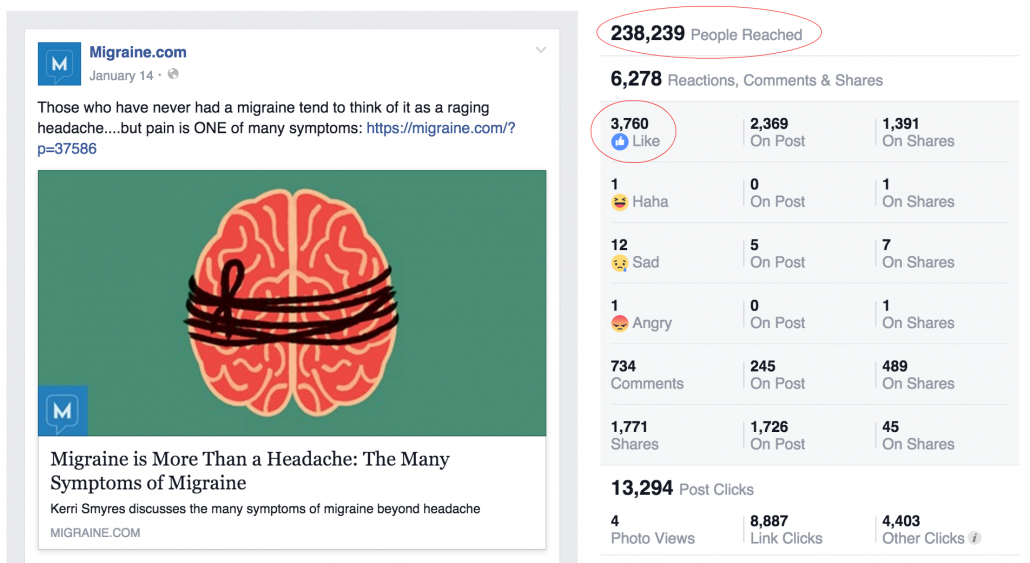

This is where condition-specific health communities join the party. Just as my riveting work stories fall flat during girls’ night out, migraine experiences would be met with empty stares on a site like ILoveDogs.com. Even a health site, like RheumatoidArthritis.net, though health-related, would still not resonate with a migraine-specific story. However, develop a group of like-minded individuals, sharing migraine misery and looking to engage with others with migraine, such as Migraine.com, and those same experiences thrive. Suddenly those stories are not only heard, they’re embraced by a supportive community that understands the struggle.

But, as always, it’s important to note that successful communities are a two-way street — content and engagement. If individual stories become too uni-directional, a community can quickly become more reminiscent of a highway and a bike path — flooded with content, but lacking the necessary interaction among members.

So now that we, as community managers, have positioned ourselves as the keepers of all patient beliefs and self understanding (no pressure there), how do we support individual story sharing while still maintaining bi-directional community engagement?

- Give them space — As I mentioned, physicians are notorious for interrupting narratives. Because of their limited time and diagnostic goals, they rarely encourage individual stories and instead prioritize close-ended questions. So people go online to be heard. Instead of jumping in immediately to comment on a community post or share, step back a bit and allow the community to engage. Chances are, the story was not complete — it was simply chapter one. Allowing the community to self-moderate some of the comments, members are able to hone their story and better articulate their true concern.

- Don’t correct, just support — Our stories are a representation of our believed self. We describe our experiences the way we believe them to be, and we use other people’s reactions and responses to further create the experience in our minds. While it’s tempting to tell someone what they need to hear, it’s likely they will reject the response and reject the community that questioned their sense of self. Encourage a safe environment with consistent moderation and enforcement community rules, and focus responses on support and the sheer fact that they’ve been heard by a community of peers (“Thank you so much for sharing; we hear you — you are not alone”)

- Feature representative stories — While not all experiences are a positive representation of the community at large, make an effort to promote the ones that are. This will not only provide a wide range of comments and support for the individual, it will also encourage others to share their experiences as well (The If she can do it, I can do it mentality). Additionally, it provides you as the community manager with a way of shaping the tone and purpose of the community.

Story telling is one the oldest linguistic activities known to man. We unconsciously express things through narrative that we would never think to express if asked directly. It can highlight hidden beliefs, and it can sensationalize self-believed fictions, but more than anything it can help us digest, comprehend, and communicate our wellness and illness.